This article was originally published in January 2018 on the now-defunct website Washington Babylon (which has since evolved into Ken Silverstein's mordantly muckraking Substack site).

The word “Science” was added to the name in 1958, possibly inspired by the National Defense Education Act of the same year, which was part of a general increase in science funding in response to the recent launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union. A domed planetarium was added to the museum at that time. Sitting in there and staring up at the "stars" is my most vivid preschool memory.

|

| Gloria Glaze, preschool teacher and director. |

|

| My teacher, Annie Riley. |

The school’s philosophy, according to Museum Director Horace Dodson “Dixie” Carmichael, was that “there is no field that cannot be introduced to a child. All you have to do is present it right.” In the late 1960s, a local newspaper noted that “Dallas County couples often enroll their children before they even are born" (3).

The purpose of the bunker was summarized by Commission Chairman John W. Mayo in a statement at the dedication ceremony, which is reproduced in the document below.

In addition to running a mortgage company (as indicated on the letterhead above), Mayo was also a local American Legion post commander—an ardent anti-Communist by definition, as indicated in the following passage from an exhibit catalog for the Dallas Museum of Art:

"In March of 1955, Col. John W. Mayo, commander of the Dallas Metropolitan Post No. 581 of the American Legion, sent a communication to the Trustees of the Art Museum decrying many of the Museum's policies and saying that the Post objected 'to the Museum patronizing and supporting artists...whose political beliefs are dedicated to destroying our way of life.'"(4)

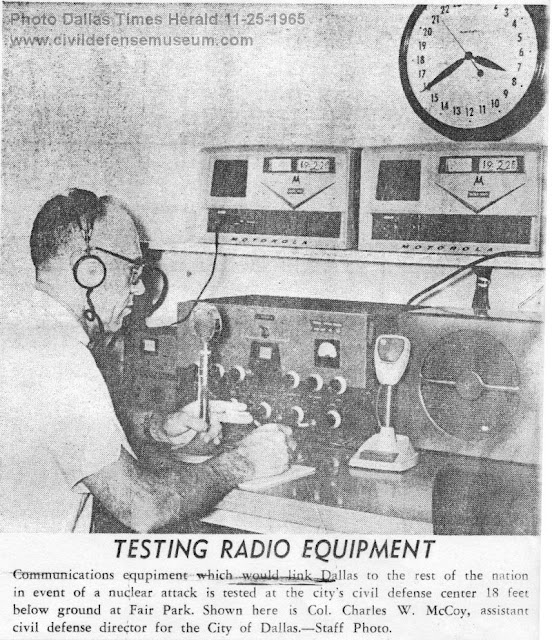

Civil Defense historian Eric Green provides details of the bunker on his Civil Defense Museum website:

"The old Dallas Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center (EOC) is located under the playground in front of the Science Place Planetarium Building at Fair Park in Dallas Tx. This EOC was to function as a relocation shelter for Dallas govt. officials in the event of a nuclear attack. It was from this shelter that officials would have tried to coordinate recovery efforts involving community shelters, radiological monitors, police, fire, sanitation and other services.

Construction of the EOC lasted from 1960 to 1961 at a cost of $120,000. The City of Dallas paid $60,000 and the Federal govt. paid the additional $60,000. This shelter is a blast shelter in the true sense of the term. It is equipped with large concrete and steel blast doors which bolt shut when closed for sealing purposes. The exterior blast door is plainly visible next to the sidewalk on the southeast side of the building.The EOC also is equipped with air ventilators containing "anti-blast valves" which would close to prevent blast pressure from entering the shelter. The air circulation system was built with a separate air filtration room complete with a wall of air filters to remove fallout contaminants from the incoming air.According to a March 27, 1962 Dallas Times Herald article the shelter was officially opened on April 1st, 1962 at 3pm. The shelter is now closed to any public access and is only used for storage purposes by the Science Place." (6)

Marilyn W. Waters was on the museum staff for 45 years, from 1961 until her retirement in 2006. In 2014 and again in 2018, I interviewed her via email about the bunker:

"It was well underway when I came and was just being completed. The then Exec. Director [H.D. Carmichael] had a background with emergency preparedness when he worked for an arm of the Red Cross. He was always interested in civil defense issues and was on some important committee dealing with Emergency Preparedness.

There was a citizen activist group connected with the then newly formed Dallas City-County Civil Defense and Disaster Commission and to the best of my recall, our Exec. Director was part of the group especially with his Red Cross Disaster Relief background.

During the Cuban Missile crisis, armed guards were placed at the entrance so that only authorized persons could enter.

It leaked like crazy—radioactivity would have seeped in the leaks! The sump pumps to force sewage up to the ground level didn’t work well so sewage backup would have been a problem.

The museum was supposed to be able to use the large meeting/planning room whenever the Civil Defense people were not having training. It was soon obsolete with the advent of the hydrogen bomb. It would have been vaporized with any strike near downtown.

Civil Defense, the fire department and the police department all at one time had emergency stations down there. When they pulled out, they left odds and ends of early 1960’s radio equipment and other items. All working engines, food stuffs etc. were removed and we were left with an interesting basement—except when the hydraulics malfunctioned on the 7 ton lead lined doors that sealed off the stairs down into the shelter! We used it for a classroom, storage and other things over the years." (7)

WRR, the museum, and the bunker have many things in common.

An online exhibit by the Dallas City Hall provides the following historical summary of WRR:

"WRR is the municipally-owned radio station operated by the City of Dallas. It not only pioneered the local airwaves; WRR was the first licensed broadcast station in Texas and the South and the second broadcast station issued a commercial license in the United States....

Licensed in August 1921, the station was originally housed in the Dallas Fire Department central headquarters, located adjacent to Dallas’ old city hall at 2014 Main Street. In 1923, WRR moved to the Jefferson Hotel, and in 1925, to the Adolphus Hotel, then to the Southland Life Building's 10th floor in the 1930s, and to Fair Park from 1936-1973 in the WRR, Police, and Fire Building now occupied by the offices of the State Fair of Texas....

Until the departments had their own internal support, WRR supplied and maintained all radio equipment for Police, Fire, Park and Recreation, Water, Public Works, and the former Health Department. At its peak it furnished dispatching services for Dallas County, Cockrell Hill Police Department, and private ambulance services (in the days before 911). WRR discontinued these adjunct services in 1969."(8)

|

| At Fair Park, with the Cotton Bowl in the background. |

In 1973, an addition to the Dallas Health and Science Museum was built as the new home of WRR. Marilyn Waters recounted that development:

"Their first location in Fair Park was in a building just off the main street of the State Fair grounds. Over time they had amassed considerable funds and wanted to build in Fair Park. The Dallas Health Museum wanted to expand. Architects came up with a plan that would give the museum more space and provide additional space for WRR, especially to house their growing operations. Eventually a second floor was completed converting the small office area upstairs into a full second floor complete with classrooms." (7)

|

| WRR building on the left, attached to the original Dallas Health and Science Museum building. The bunker is on the opposite side of the museum building. |

|

| Front entry to the WRR building. |

THE JFK CONSPIRACY CONNECTION

"In April 1, 1962, Dallas Civil Defense, with Crichton heading its intelligence component, opened an elaborate underground command post under the patio of the Dallas Health and Science Museum. Because it was intended for “continuity-of-government” operations during an attack, it was fully equipped with communications equipment.With this shelter in operation on November 22, 1963, it was possible for someone based there to communicate with police and other emergency services. There is no indication that the Warren Commission or any other investigative body or even JFK assassination researchers looked into this facility or the police and Army Intelligence figures associated with it."(10)

Peter Dale Scott, an eminent JFK assassination researcher who coined the term "deep state" to describe those in the federal executive bureaucracy who allegedly wield inordinate power behind the scenes, attributes to Crichton a prominent role:

"Since World War Two, secrecy has been used to accumulate new covert bureaucratic powers under the guise of emergency planning for disasters, planning known inside and outside the government as the 'Doomsday Project.' Known more recently as 'Continuity of Government' (COG) planning" it was "originally concerned with decapitation of the US government after a nuclear attack.... All this Doomsday planning can be traced back to 1963, when Jack Crichton, head of the 488th Army Intelligence Reserve unit of Dallas, was also part of it. This was in his capacity as chief of intelligence for Dallas Civil Defense, which worked out of an underground Emergency Operating Center." (11)

Scott adds: “Six linear inches of Civil Defense Administrative Files are preserved in the Dallas Municipal Archives. I hope an interested researcher may wish to consult them.” (12)

In the meantime, we can consult Marilyn Waters, who was working at the museum, above the bunker, on the day JFK was assassinated:

"My boss at the time, H. D. Carmichael, had one of the limited invitations to attend the luncheon where Kennedy was to speak. He was very excited about the opportunity. Once he left the building to drive to the Trade Mart, I hopped in my car to go over a couple of blocks to get a plate lunch. For some reason on that day, I didn’t turn on the radio but just headed back to work. The minute I walked in, other staff members immediately began to try to tell me what had happened. It was so shocking, so unbelievable, we just stood around looking at each other. We were not sure if this was a part of a major conspiracy or what." (9)

Waters was aware that Dallas was a hotbed of paranoid right-wing activity in those days. “Nut country,” as JFK reportedly called it. She continues:

"Meanwhile, my boss was waiting with a thousand others at the Trade Mart for the president to arrive. An announcement was made to those waiting that the president had been shot. My boss was a canny old field news reporter and knew people with press passes. He managed to get in with the press and get out to Parkland Hospital to the Emergency Entrance. I don’t think that he ever got inside, just to the entrance. He was there when they made the final pronouncement. He shared all this with us back at the museum via phone." (9)

So, was there any unusual activity at the bunker when JFK was shot? “No, we didn’t notice anything suspicious about the shelter on that ominous day,” Waters says. “We racked our brains later trying to think but nothing came up.” (9)

(2) Irene Field Carmichael, About the Musuem (Dallas Health and Science Museum, 1973). Irene Carmichael was the second wife of H. D. “Dodson” Carmichael.

(5) jfk-research.org

(6) Eric Green, Civil Defense Museum.

(10) Russ Baker, Family of Secrets: The Bush Dynasty, America's Invisible Government and the Hidden History of the Last Fifty Years (2009), 120-21.